OWASP Top Ten - Injection

If you want to learn about Web Application Security, you’re going to need to know the OWASP Top 10 - a list of the most critical security risks to web applications compiled by the OWASP (Open Web Application Security Project) Foundation.

We’re going to dive into the first vulnerability on that list - Injection.

All examples of potential attacks in this article are for demonstration and educational purposes only. They should never be used outside of a lab environment or to harm other computers, users, etc.

Let’s say you’re on a website and you visit the login page. If you’re a regular user, the kind developers adore, you’ll enter your correct username and password and easily log in.

What if you’re not a regular user, though? What if you’re an attacker trying to see what information you can steal or you’re looking to break into an administrator account? Well, the login page is a great place to try an injection attack.

Why? Because the login page relies on some kind of database or other authentication server. This server has a language of its own (often SQL, but it could be a NoSQL, LDAP, or other type of application).

The code gets the username and password - from the user - and uses those values to find the right user in the database. If the data provided by the user isn’t properly cleaned/sanitized, a malicious user could put some of their own code in the username and/or password fields.

Depending on how the code is written, the server receiving the login request doesn’t know which stuff is from the user and which is code written by the developer, so it all gets run as legitimate code.

How Likely Is It?

Luckily, injection is not as common as it used to be. Most developers are trained to use more secure practices nowadays, but it can still happen. Often you’ll find injection risks in legacy code or software that builds the queries for the developer. Even though it’s not as common, it’s still a threat and a big one at that.

How Bad Is It?

If your code is unlucky enough to be vulnerable to injection, malicious actors can do a LOT of very bad things (bad for you, not for them).

- They can view, corrupt, and steal your data

- This opens you up to a bunch of other problems (hefty fines, loss of customer trust, identity theft issues, etc)

- Malicious actors can use injection to prevent others from accessing your system with a DoS (Denial of Service) attack

- They can even use injection to gain a foothold in your system and from there infiltrate your entire network

So even though injection vulnerabilities are not as common (OWASP rates their prevalence at a 2), they have not completely disappeared and the potential impact of one can be very severe.

How Do Attackers Get In?

“Almost any source of data can be an injection vector, environment variables, parameters, external and internal web services, and all types of users.”

Unfortunately, this means there are lots of ways attackers can get in.

Some of the most common types of injection attacks:

- SQL

- NoSQL

- LDAP

- XPath

- OS commands

- SMTP headers

To understand the basic idea behind injection and how you can prevent it, we’re going to show a very basic example using SQL.

After that we’ll briefly discuss NoSQL injection. Then we’ll touch on the other 4 areas it commonly occurs (LDAP, XPath, OS commands, and SMTP headers). Each section will contain links to additional sources for you to learn more.

SQL Injection (aka SQLi)

SQLi is probably the most common injection vulnerability web developers will need to fully understand and try to prevent.

When a web developer wants to talk to a relational database, they use SQL (Structured Query Language) - or an API (Application Programming Interface) or ORM (Object Relational Mapping) tool which converts their code into SQL. We won’t discuss APIs and ORMs here except to recommend that you use them (instead of building your own SQL queries) and to warn that even they can have injection vulnerabilities since they build SQL statements.

For our example, let’s pretend the web developer is not using best practices and is writing their own SQL code to talk with the database.

In that case, our basic SQL statement looks like this:

SELECT name FROM users WHERE username='katie' AND password='verystrongpassword';

This is a very simplified example of the code that might be run when you enter your username and password in a login page.

This code tells the database, “find the person with a username of ‘katie’ and a password of ‘verystrongpassword’ and give me their name back”. Often, it’s more complicated than this, but this gives you a basic idea.

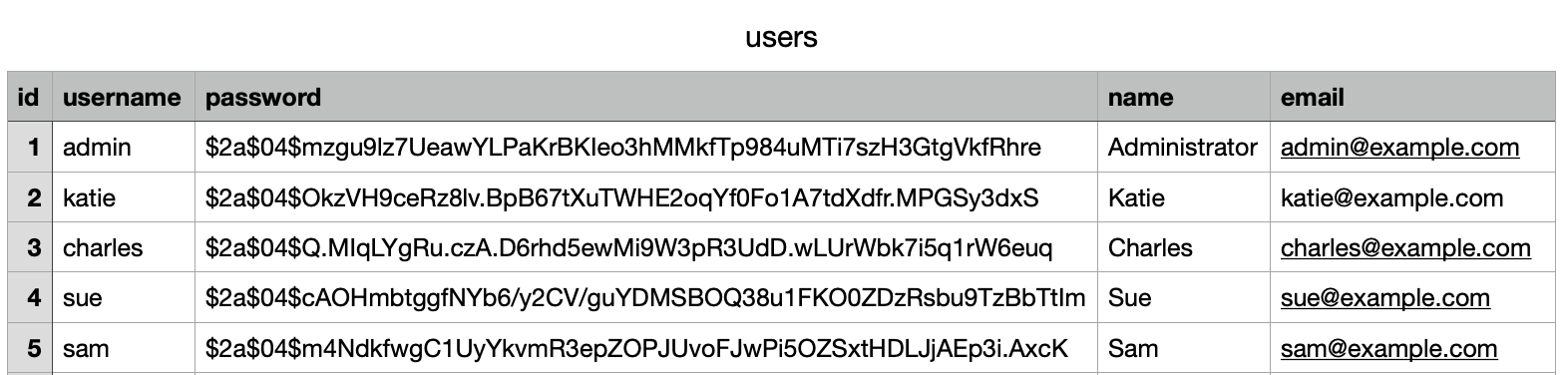

To help you understand, picture all the user data in a relational database as a spreadsheet.

In our SQL statement, some words are in ALL CAPS. These are the SQL keywords (SELECT, FROM, WHERE, AND). These keywords mean something very specific and are different from the others, though it’s not required that they be written in ALL CAPS.

SELECT name

The SELECT keyword means I want the database to return a specific field (or list of fields).

name is the field (like a column in a spreadsheet) I want the database to give me.

FROM users

The FROM keyword tells the database which table to look in.

users is the name of our table (like the name of a spreadsheet).

WHERE username=’katie’ AND password=’verystrongpassword’

The WHERE keyword means I only want the record that matches.

username is the first field (column) we are matching.

‘katie’ is the text it should match.

The AND keyword means both fields must match.

password is the second field we need to match.

‘verystrongpassword’ is the password value we’re looking for.

You may notice we don’t have any passwords in the table that look like ‘verystrongpassword’. That’s because it’s best practice to salt and hash passwords before storing or looking for them in the database.

In this specific example, we would expect to get the text ‘Katie’ back from the database.

; (semicolon)

The ; tells the database this is the end of the SQL statement.

Different Parts Do Different Things

It’s important to understand the different parts of a SQL statement mean, and do, different things.

You can think of them like different pieces in a machine.

- The SQL keywords are there to tell the database WHAT you want it to do

- The tablename (e.g.

users) is WHERE it should look - The fields (e.g. name, username, password) are where IN THE TABLE we’re looking for a match and want to return data from

- The data we get from the user (e.g. ‘katie’ and ‘verystrongpassword’) are WHAT values we’re looking for to find the correct record

Exploiting Injection

If SQL was always separated into these separate bits, we wouldn’t have to worry about injection. Unfortunately, us humans - not computers - write code so we try to make things easier for ourselves.

Instead of separating out the different bits of a SQL statement, developers can build one out of a text string.

Let’s say I wanted to build the above SQL statement from text and put it in a variable.

I have 2 variables that have the username and the hash of the password the user submitted:

$username and $password.

Now I can just plug them into a text string to “build” a SQL statement

$sql = "SELECT name FROM users WHERE username='" . $username . "' AND password='" . $password . '";

When I pass this text string to the database, now the database will have to figure out which pieces it thinks are SQL and which are tables, fields, and data. That’s where SQL injection gets exploited.

Injecting Code

Like we’ve seen, there are special keywords and characters that let you do specific things in SQL.

Instead of a user entering the text katie into the username field, what if they entered:

katie' OR 1=1;--

With that as the username, our text string to “build” a SQL statement now looks like this:

SELECT name FROM users WHERE username='katie' OR 1=1;--

That’s because we entered a few special characters and keywords that are actually SQL code.

'(single quote) character- this closes out the username text

OR 1=1- this tells the database to give me ALL the names from the users table because 1=1 is always true and now we’re not specifying which record to return, it will return all of them

;(semicolon)- this ends the SQL statement early

--(2 dashes)- this comments out everything else after it and means the database won’t even check the password field at all

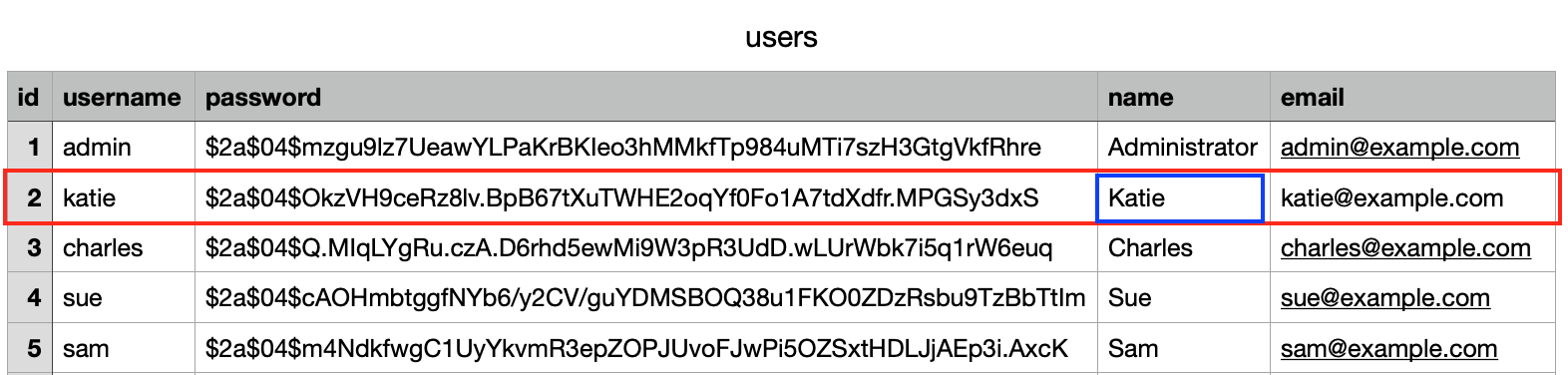

Instead of getting back the name ‘Katie’ from the database, now we’ll get back ALL the names:

- Administrator

- Katie

- Charles

- Sue

- Sam

What if this code didn’t just return the name of the user? What if it returned their name AND logged them in?

With this injection vulnerability ANYONE could log in without having a valid username or password.

Basic Idea Behind ALL Injection

Granted, this is one very simple way to inject code into a very basic, unprotected SQL statement. Most scenarios will not be this simple, but they still follow the same premise.

- Statement is being built with user-supplied input

- User-supplied input is not properly formatted/sanitized to clearly delineate code from user-supplied data

When you get data from users (or anywhere outside your own code), assume it’s malicious. Because I guarantee that someone, somewhere, will try to use it maliciously.

Further Reading

Possible Ways To Help Prevent SQL Injection

Advice gathered from OWASP’s SQL Injection Prevention Cheat Sheet

Use Prepared Statements (with strongly typed parameterized queries)

Prepared statements with strongly typed (looking at you PHP) parameterized queries is the BEST defense against SQL injection. Tools to create prepared statements (usually) clearly separate code and user-supplied input so that input doesn’t end up acting like code. Do your research to find a good and secure option for your language.

If you use an API or ORM - excellent options you should definitely consider using - remember they can also be vulnerable to SQLi. Someone wrote code that builds the SQL statements. Depending on how it’s written, an injection vulnerability could be lurking inside.

Do diligent research on the tool before you use it. Implement multiple layers of defense (such as regularly updating your libraries, implementing Least Privilege, using LIMIT on your queries, and the options below) to help catch vulnerabilities you don’t know about.

Use Positive/Goodlisting

Previously known as whitelisting, this option is necessary if you can’t bind variables, but also a good idea whenever you can use it.

Don’t let users enter just anything. For example, if you have a stored procedure where you need the user to supply the table name since you can’t bind it, check what the user gave you against a list of known table names. If it doesn’t match one of the pre-approved table names, return an error.

At Minimum, Properly Escape All User-Supplied Input

This might be your only option if you have a large legacy system and it’s not worth the cost to secure it properly. Properly escaping/sanitizing user input will help but is not a guarantee and can be tricky depending on your setup. Only use it as a last resort or in addition to the options above.

If this is your only option, check out the OWASP ESAPI as a more secure alternative.

Further Reading

- How can prepared statements protect from SQL injection attacks? - via StackOverflow

- Bobby Tables - A guide to preventing SQL injection

Non-SQL Based Injection

While SQL is only one type of injection, it illustrates the basic idea behind injection attacks:

- Server-side code receives input from the user

- The server sees it as legitimate code and executes it

If the input is not properly handled, malicious attackers can run code on your server.

We won’t go into detail on all the other types of injection, but we will offer a brief explanation and resources for you to learn more.

NoSQL Injection

NoSQL databases don’t mean “No SQL”. NoSQL means they are a non-relational database. There are many types of NoSQL databases to choose from and they’re all different.

Like relational ones, NoSQL databases each use some type of query language. If the query is dynamically created from user-supplied input (like getting the username and password from the user before logging in), it could still be vulnerable to injection.

Every NoSQL database is different and has its own risks. Just because they don’t use SQL does not mean they don’t have injection vulnerabilities. Properly research the database you’re using to see if any vulnerabilities have been found.

Further Reading

- Testing for NoSQL Injection

- NoSQL Injection (using MongoDB as an example)

- Preventing NoSQL Injections (near the end of the article)

LDAP Injection

If you’re authenticating with an LDAP (Local Directory Access Protocol) server, and taking username/password info from a user, it could be vulnerable to injection.

Further Reading

XPath Injection

When your database is an XML (eXtensible Markup Language) file, instead of using SQL you’ll use XPath. If you’re dynamically building the XPath query from user-supplied input, it can be vulnerable to injection.

Further Reading

OS Command Injection

If user-supplied input is used to run OS commands, that code can be vulnerable to injection.

Further Reading

SMTP Headers Injection

If a contact web form is used to dynamically create emails, if it doesn’t have proper controls and sanitization it can be vulnerable to injection.

Further Reading

Possible Ways To Help Prevent Injection

If you want to protect yourself against possible injection attacks, you need to know where you might be vulnerable.

Manual Code Reviews + SAST

Help train new developers, and remind seasoned ones, how to prevent injection vulnerabilities with documented secure development guidelines. Other good practices, like code reviews and pair programming, can bring more eyeballs to the code and help discover possible vulnerabilities.

Integrating SAST (Static Application Security Testing) into your development cycle can also help developers find known security flaws before the application goes to QA.

A SAST tool should always be used in conjunction with secure coding practices. Neither will find all vulnerabilities, but by doing both you have a much better chance of discovering vulnerabilities BEFORE they go to production.

Testing: Fuzzing + DAST

Automated testing, including fuzzing, can help find injection vulnerabilities in the following places (and more):

- parameters

- headers

- URL

- cookies

- JSON, SOAP, XML data inputs

Fuzzing will help you find unknown vulnerabilities. Fuzzing software throws random data at your application to see how it responds. It can be a valuable tool in your testing arsenal for finding injection and other vulnerabilities.

Integrating a DAST (Dynamic Application Security Testing) tool into your CI/CD (Continuous Integration/Continuous Development) pipeline can help find known security flaws in a fully functioning application before it’s released to production.

For example, if you’ve just integrated an API or ORM with a known injection flaw (that you weren’t aware of), a DAST tool can help find the vulnerability BEFORE you release your app to the world.

Regularly Updating

As always, keeping your third-party software updated helps prevent known vulnerabilities from being exploited. It’s a simple (most of the time) and commonly overlooked step, but regularly updating will save you a lot of headache.